Toronto at Home: Building on Shifting Ground

TWIG

8 July 2025

Preface

Toronto’s housing crisis is receiving unprecedented attention among citizens and policy makers alike as home prices soar and rents skyrocket. The average price of a home in Toronto has more than tripled since the early 2000s, far outpacing income growth and leaving many aspiring homeowners locked out of the market. Renters fare no better, with average rents for a one-bedroom apartment now exceeding $2,500 per month, forcing many to spend over 50% of their income on housing. The crisis is exacerbated by limited housing supply, restrictive zoning laws, and a lack of affordable family-oriented housing or purpose-built rentals. Compounding the issue, a persistent shortage of construction workers from the 2010s to 2023 slowed the pace of new housing development, even as demand soared. With homelessness on the rise and low- to middle-income families being displaced to the fringes of the city, Toronto’s housing market is no longer just unaffordable—it is unsustainable.

‘When a Place to Live Became an Investment’ is the first in a four-part series that explores the evolution of housing in Toronto, unpacking its history, its current challenges, and potential pathways forward. This first article examines how homeownership has transformed from being a place to live into high stakes/high return investments, reshaping affordability and accessibility for residents. The second article dives into Toronto’s housing history, tracing the evolution of building styles, forms and construction costs that have both come to define and redefine the city’s skyline and neighborhoods over the decades. The third article investigates how housing trends have influenced the types of employment available in the construction industry, altering the types of jobs, skills, and labour demands to meet Toronto’s ever-growing housing needs. Finally, the series concludes with a forward-looking exploration of alternative housing models, their potential to address the city’s housing crisis, and their profound implications for the construction workforce of the future.

No single solution—whether housing types, policy changes, or financial interventions—will fully resolve Toronto’s housing crisis overnight or even over the next decade. The hard truth is that true affordability would require a real estate crash akin to the early 1990s—an outcome that would wipe out the generational wealth of approximately 1.5 million Toronto homeowners. Instead, the challenge lies in finding a balanced path forward—one that expands housing access without undermining economic stability. We hope that Toronto at Home contributes to a genuine conversation about how to move forward.

Introduction

While housing prices in the city have shown signs of cooling in 2025, this has not been accompanied by an increase in supply. In fact, building permit data from Statistics Canada shows a marked decline in residential construction intentions across the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (CMA), suggesting that the pipeline of new units is drying up. As a result, affordability may only worsen over time due to constrained supply rather than having a genuine price correction. At the time of this writing, the Province of Ontario still estimates that over 2 million homes will need to be built by 2031 (CBC 2025).

As highlighted in TWIG’s Toronto at Home (2025), the cost of land is now the dominant driver of housing unaffordability in the city. In our first report, in most Toronto neighbourhoods, over 50% of the cost of a new home is attributable to land alone. Without a strategy to unlock public lands held by all order of government—municipal, provincial, and federal—most affordable housing proposals will remain financially unviable.

Furthermore, development charges and community benefit fees add upwards of $200,000 per unit to the costs. While designed to fund critical infrastructure and community services, these fees often delay or derail otherwise feasible affordable housing projects. A targeted reduction or exemption policy—applied to non-profit and deeply affordable developments—is urgently needed.

Finally, political leadership must recognize that introducing below-market housing at scale will inevitably put downward pressure on the value of existing homes. This effect is particularly acute in neighbourhoods with inflated real estate valuations. Though politically sensitive, this shift is necessary to restore balance to a system in which shelter has become more asset than necessity.

New Forms of Construction – Can It Be Faster, Greener, and Cheaper?

As Canadian cities like Toronto grapple with acute housing shortages and rising construction costs, alternative building technologies have come under renewed scrutiny. While conventional construction methods remain dominant, several emerging or underutilized approaches offer the potential for lower costs, faster build times, and greener outcomes. This piece explores the feasibility of three leading alternatives—modular and prefabricated housing, mass timber, and 3D printing—while acknowledging the barriers to scaling them in dense urban environments.

Modular and Prefabricated Housing: Fast-Tracking Affordability? Modular housing involves constructing sections of a building off-site in a controlled factory environment, which are then transported and assembled on-site. This process can reduce construction timelines by up to 50% and minimize weather-related delays and on-site waste.

Toronto has implemented this model through its Modular Housing Initiative, which launched in 2020 to address chronic homelessness. While the program successfully built several hundred units on city-owned land, the average cost per unit has hovered around $350,000–$400,000, raising questions about whether modular delivers meaningful affordability. The cost savings reflect not just construction but also land preparation, design, and servicing expenses.

Other municipalities have explored modular more aggressively:

- Vancouver’s Temporary Modular Housing Initiative rapidly added units for the unhoused using a leasing model on city land, minimizing capital costs.

- Montreal and Hamilton have examined modular expansions for seniors and transitional housing, but few projects have scaled up.

- In Europe, countries like the Netherlands and Sweden use modular for student and migrant housing at significantly lower per-unit costs—facilitated by centralized planning and lower land prices.

In Toronto, significant barriers remain:

- Urban Logistics: Dense traffic, narrow streets, and limited staging areas constrain modular delivery and assembly.

- Land Use Constraints: Without large, undeveloped land parcels, large-scale modular housing is difficult to deploy.

- Transportation Costs: Hauling prefab units into the city adds costs that may offset savings.

Checklist for Modular Housing:

| Objective | Assessment |

| Affordability | High per-unit cost in Toronto, could change if built to scale |

| Speed of Construction | Proven time savings |

| Carbon Reduction | Mixed depending on transport and materials |

Mass Timber Construction: Greener and Mid-Rise Friendly

Mass timber—engineered wood products like cross-laminated timber (CLT) and glue-laminated beams—offers a sustainable alternative to concrete and steel. Ontario’s updated building code now permits mass timber structures up to 12 storeys, opening new possibilities for mid-rise development.

Prominent examples include:

- Limberlost Place at George Brown College: A 10-storey institutional project serving as a flagship for mass timber in Toronto.

- Brock Commons in Vancouver: An 18-storey student residence that, until recently, was the tallest mass timber building globally.

- Origine in Québec City: A nine-storey residential tower showcasing Quebec’s investment in timber technologies.

Despite its benefits, mass timber remains costly:

- Per-square-foot construction costs remain similar or slightly higher than concrete due to limited economies of scale.

- Insurance premiums and financing terms are less favorable, particularly for residential developers.

- Labour shortages in skilled timber framing remain a bottleneck. Although this could be changing due to the significant slowdown in construction employment.

Checklist for Mass Timber:

| Objective | Assessment |

| Affordability | Comparable or higher build costs |

| Speed of Construction | Neutral benefit |

| Carbon Reduction | Strong sustainability credentials |

3D-Printed Housing: The Long-Term Frontier 3D printing uses concrete or composite materials to print building components layer by layer. This technique is still experimental in Canada but has attracted global attention for its potential to rapidly produce low-cost, resilient homes.

International examples include:

- ICON in Texas: Completed multiple 3D-printed homes, including entire communities for veterans.

- COBOD and PERI in Europe: Delivered multi-storey buildings in Denmark and Germany.

- India’s TVASTA: Used 3D printing for disaster-relief housing at a fraction of traditional costs.

Toronto’s hurdles include:

- Regulatory Uncertainty: Building codes and permitting processes are not yet adapted for 3D printing.

- Urban Compatibility: The technology is currently better suited to low-rise, suburban or rural environments.

- Demonstration Gaps: No major pilot projects have been initiated in Ontario.

Checklist for 3D Printing:

| Objective | Assessment |

| Affordability | Potential, but unproven in Toronto |

| Speed of Construction | High once operationalized |

| Carbon Reduction | Depends on materials and techniques |

Conclusion: A Portfolio Approach to Innovation

While none of these technologies alone can solve Toronto’s housing crisis, each contributes a piece of the puzzle. Modular construction offers speed and flexibility; mass timber delivers sustainability and mid-rise potential; and 3D printing opens long-term innovation pathways. However, early efforts have not delivered true affordability, and costs remain high relative to expectations. Without addressing land prices, permitting bottlenecks, and workforce capacity, innovation in materials and methods will have limited impact. Policymakers must prioritize between goals—speed, cost, or carbon—because achieving all three simultaneously may be unrealistic. The key is to treat these approaches not as silver bullets, but as components in a broader, more coordinated strategy that includes public land use reform, financial innovation, and sustained government leadership.

Final Perspective: A Note of Caution on Innovation

Housing is too important a social need to be left entirely to unproven technologies or speculative hopes. Policymakers must clearly define which objective they aim to prioritize—whether that’s reducing emissions, speeding up construction, or improving affordability of homes. Attempting to solve all three simultaneously risks achieving none.

Toronto’s recent experience with delayed infrastructure projects like the Eglinton Crosstown LRT serves as a cautionary tale. Innovation can introduce new delays, budget overruns, or quality concerns, especially in extreme weather conditions like Toronto’s. If deployed too quickly or at the wrong scale, some solutions could be more expensive than conventional construction and burden residents or governments with unforeseen maintenance costs. In the face of a housing crisis, bold thinking is needed—but so is pragmatism, especially when public dollars and public trust are on the line.

Leasing Models and Community Ownership – Just in Time or Too Little Too Late?

Non-market housing solutions have re-emerged as credible options in light of persistent affordability crises. These approaches prioritize permanence, democratic management, and long-term affordability, yet require substantial political and financial support to scale.

Co-operative Housing: Toronto has an over 40-year history of successful co-ops, yet very few have been created since the 1990s. New co-ops like the Hugh Garner Housing Co-op’s proposed infill expansion in Cabbagetown demonstrate interest but remain entangled in zoning and funding delays. Provincial and federal support under past programs like the Co-operative Housing Incentive Program (CHIP) must be revived with a focus on rapid approvals.

Community Land Trusts (CLTs): nonprofit, community-based organizations that acquire and steward land for the purpose of providing permanently affordable housing or other community assets. In Toronto, the Parkdale Neighbourhood Land Trust (PNLT) is a leading example. Since 2014, PNLT has successfully acquired and managed multiple buildings, removing them from the speculative market and preserving affordability in one of the city’s most at-risk neighbourhoods. Yet, despite its success, PNLT’s efforts remain relatively small in scale due to policy and financial constraints.

In the grand scheme of Toronto’s housing and real estate market, community land trusts (CLTs) still represent a relatively small but growing response to affordability and displacement pressures. The Parkdale Neighbourhood Land Trust remains one of the city’s most established examples, acquiring properties to protect affordable housing and community spaces in Parkdale. Other efforts, like Circle Community Land Trust, which manages over 600 scattered homes formerly owned by Toronto Community Housing, and the Toronto Islands Residential Community Trust, which safeguards the affordability of homes on the islands, demonstrate how CLTs can function at scale — though these still account for a fraction of the city’s overall housing stock. Kensington Market, Chinatown, and Little Jamaica each have smaller, neighbourhood-based land trusts working to protect cultural identity and affordable spaces, but they too operate within the narrow margins permitted by Toronto’s real estate landscape.

In neighbourhoods like South Etobicoke and along Eglinton Avenue West, community-led efforts to establish land trusts are gaining momentum, though these are still in early stages. The Community and Cultural Spaces Trust (CCST) has made important strides in protecting affordable arts and cultural spaces, but their portfolio remains modest. Across the city, CLTs rely on grassroots organizing, community partnerships, and often public support to acquire land and buildings — but in a city where private real estate investment dominates, their capacity to significantly shape the market remains limited. Their strength lies not in scale, but in offering targeted, permanent solutions for specific communities at risk of displacement.

The key strength of the CLT model lies in its separation of land ownership from building ownership. Residents lease the land under their homes from the trust, which ensures that resale values remain affordable and that land remains permanently in community control. This approach protects against displacement, speculation, and escalating housing costs.

Scaling CLTs in Toronto, however, faces three main barriers: the absence of mechanisms for public land transfers, lack of financing for land banking, and insufficient recognition in municipal planning processes. Without dedicated funding streams or policy supports, CLTs struggle to compete with private developers in the land acquisition market.

Internationally, CLTs have gained traction in jurisdictions grappling with similar affordability pressures:

Burlington, Vermont: The Champlain Housing Trust, founded in 1984, is the largest CLT in the U.S., serving over 6,000 residents. It has received sustained state and municipal support and uses layered subsidies to ensure affordability over generations.

Denver, Colorado: The Urban Land Conservancy has adapted the CLT model for use in mixed-income housing and transit-oriented development. It acquires land near public transit nodes, preserving it for long-term affordability while partnering with housing providers.

Vancouver, British Columbia: The Community Land Trust Foundation of BC, backed by the Co-operative Housing Federation of BC, has acquired and developed hundreds of affordable units. Crucially, it has benefited from city land leases and access to provincial housing funds.

These examples show that where governments actively partner with CLTs—by providing land, capital, and regulatory clarity—the model can scale effectively and offer a durable solution to housing affordability. In contrast, without such support, Toronto’s CLTs risk remaining underpowered despite strong grassroots demand.

CLTs present a clear opportunity to reframe land as a shared resource, not a speculative asset. They align closely with the public interest and offer one of the most resilient structures for preserving affordability over the long term. For Toronto to capitalize on this model, a dedicated city-wide land acquisition strategy and a provincial CLT development fund should be established.

Public Leasing Models: The City’s “Housing Now” initiative aims to lease surplus public land for mixed-income development. While the goal is laudable, delays, high parking requirements, and mixed execution have slowed progress. Successful public leasing requires streamlined timelines and consistent incentives. International examples, such as Singapore’s 99-year leases, offer insight into how public land can be used as a permanent affordability tool.

Can Toronto Learn from Singapore’s Public Housing Model?

Among global housing systems, Singapore stands out as the most effective large-scale model of public land stewardship and widespread affordability. Through its Housing & Development Board (HDB), the Singaporean government houses over 80% of the population, with roughly 90% of these households “owning” their homes through 99-year state-issued leases. This system has enabled dense, high-quality, and inclusive development without land speculation.

However, for Toronto, replicating this model would face significant hurdles:

- Land Ownership: Unlike Singapore’s 90% state-owned land base, Toronto has limited public land. The financial and political costs of acquiring land at scale are prohibitive without intergovernmental support.

- Governance Structure: Singapore’s centralized decision-making allows for long-term planning. In Toronto, housing policy is shaped by a fragmented system of municipal, provincial, and federal actors, each with competing priorities.

- Ownership Norms: Canadian cultural norms strongly favour freehold ownership and unrestricted resale. In contrast, Singapore normalizes leasehold and enforces resale controls to maintain affordability.

- Legal Constraints: Introducing strict occupancy requirements, price caps, or ethnic integration rules—as Singapore does—would be legally complex and politically sensitive in Toronto’s context.

- Financing Tools: Singapore leverages its Central Provident Fund (CPF)—a mandatory social savings system—to finance home purchases. No comparable mechanism exists in Ontario.

Despite these challenges, Singapore’s model offers important lessons. Toronto can adapt select elements such as:

- Long-term land leasing on public sites.

- Mixed-income developments with affordability guarantees.

- Centralized planning frameworks tied to transit and infrastructure.

- Use of land value capture to fund housing and community services.

Rather than direct replication, Toronto could pursue a hybrid approach that blends Singaporean-style planning discipline with local community land trusts, co-ops, and public-nonprofit partnerships. These efforts must be underpinned by a commitment to long-term affordability, active land policy, and recognition that the current speculative model is incompatible with inclusive urban growth.

We Told a Generation to Go into the Trades – Now We Must Deliver

For the past decade, the Ontario government and its education and workforce partners have aggressively promoted the skilled trades. Campaigns across school boards, workforce agencies, and government departments have encouraged young people to pursue apprenticeships in construction, promising stable work, good pay, and long-term careers. But this promise now hangs in the balance.

Construction Activity in Free Fall: Toronto has seen an 80% decline in construction job postings over the past two years, alongside an 8% drop in construction employment. Apprentices require on-the-job training to progress, yet increasingly, they find no employers to sponsor or no jobs to place into. Thousands of training hours, government dollars, and hopes of stable careers risk being squandered.

Housing as a Tool for Labour Market Stability: Toronto’s housing strategy must now double as a labour market intervention. We must target housing builds in areas where apprentices can be placed and matched with experienced journeypersons. Incentivizing public infrastructure—including housing—that embeds apprenticeship ratios could serve both housing supply and employment goals.

Make Good on the Trades Promise: If government encouraged a generation into the trades, it must now provide the conditions for them to succeed. Housing construction—particularly public and non-market builds—must be fast-tracked to stabilize both shelter and employment. This means releasing land, aligning procurement with union training goals, and planning housing not as a commodity but as essential public infrastructure.

Toward a Cohesive Strategy

As Toronto at Home underscores, the city must reconcile its aspirational housing targets with the tools it actually deploys. Without freeing up public land, revising cost barriers like development charges, and ensuring that new housing supports the tradespeople we trained to build it, we will continue to fall short.

Solving Toronto’s housing crisis is not only about innovation or investment returns. It’s about completing the circuit that started when Ontario promised young people meaningful work in the construction trades. That promise now demands follow-through—through large-scale, coordinated public infrastructure investments, including housing. We must act not just to meet housing demand, but to protect the integrity of our workforce and the social contract we’ve built around opportunity and affordability.

World-Class City. World Class Rent

Toronto has long aspired to be recognized as a world-class city, one that ranks among the top global hubs for finance, technology, medicine, and culture. Former mayor John Tory, as did his predecessors, described Toronto as “the best city in the world” and supported efforts to elevate its status alongside cities like London, New York, and Tokyo. But striving to be world-class comes with world-class costs. As housing prices and rents rise, it’s critical that affordability debates situate Toronto within its global peer group, not just in comparison to other Canadian cities.

In Canada, homeownership has traditionally symbolized success and security. Renting, by contrast, is often seen as temporary or second-best, something to be outgrown on the path to ownership. Popular discourse reinforces this view, with phrases like “paying someone else’s mortgage” casting renters as financially immature. Yet this narrative ignores how Toronto’s housing market has transformed over the past two decades, prioritizing real estate as an investment vehicle over livability and long-term community stability. As detailed in Part I of ‘Toronto at Home’, this shift has driven up home prices beyond the reach of many residents and increased reliance on the rental market.

Still, renting remains oddly absent from many affordability discussions or is treated as interchangeable with home prices. Headlines frequently conflate the two, e.g., ‘Toronto’s High Rent and Housing Costs Have Created a Crisis’ (Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2023) without differentiating the dynamics unique to renters. Yet, among 16 global cities analyzed, Toronto ranks 12th in terms of the share of households that rent, with 48.1% of households renting, well below global renter-majority cities like Berlin (84%), Vienna (82%), New York City (70.2%), and Paris (65.3%), but slightly higher than Stockholm (43%) and far above Singapore (9.2%). This reflects Toronto’s cultural emphasis on homeownership, even as the economic reality of buying has become unattainable for many. Yet when examining rental affordability, Toronto performs better: the average renter household spends about 30.9% of income on rent, which ranks 5th lowest among the 16 peer cities. Average renters in New York, Boston, and Vancouver pay significantly more relative to their income, often upwards of 60–100%. This contrast challenges the dominant narrative that Toronto is among the most unaffordable cities for renters. In fact, Toronto’s rent burden is more moderate compared to many of its global peers, suggesting that while housing pressures are real, rental affordability in relative terms may be more manageable than often portrayed. Still, with nearly half the city renting, ensuring an adequate supply of diverse, high-quality rental housing remains critical to supporting Toronto’s workforce and maintaining economic competitiveness.

Toronto Rental Market Affordability. Will it Last?

Toronto’s housing market has notably cooled since 2022 highs. Sales volumes in early 2025 are well below last years levels and inventory is at multi-decade highs (buyers’ market conditions). For example, April 2025 GTA home sales (5,601 transactions) were about 21% lower year-over-year, even as active listings hit a record 27,386. However, prices have only edged down a few percent in response. In Toronto proper, the median house price was $950,000, down 3.2% from the previous year. Overall, these indicators suggest modest price declines and abundant supply as of spring 2025. In tandem, the rental market has also softened as supply has risen. Vacancy rates have climbed (Toronto’s vacancy was about 3.7% in Q1 2025) while rents only recently started to decline.

Between 2022 and 2024, Toronto experienced a significant increase in purpose-built rental (PBR) housing completions. Notably, in the first quarter of 2025, 2,136 PBR units were completed, marking a 173% increase compared to the same period in 2024 and representing the second-highest quarterly total in the past 30 years. This surge in completions contributed to a 2.5% expansion of the rental stock within the City of Toronto in 2024. This is good news for renters. However, despite this uptick in completions, the initiation of new PBR projects have come to a standstill. To date in 2025, only 731 PBR units commenced construction in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA), a 60% drop from the same period in the previous year and 41% below the five-year average. This slowdown is attributed to factors such as high financing costs, declining rents, and increased competition from condominium rentals, which have made new PBR developments less financially viable. Indeed, some of the easing of rental costs have been driven by the growth of active condo rental listings, which are up 29% above last year’s level, and average condo rents fell 2.8% year-over-year in Q1 2025 (urbanation.ca). However, these condo rental units are not guaranteed to stay on the market. By policy the City of Toronto does not treat condo units as permanent rental housing and analysts warn that investor-owned condos are likely to subsequently revert to owner occupied use (chra-achru.ca). So, although investor-owned condo rentals have eased pressure in the short term, they can be withdrawn or sold at any time, unlike purpose-built rental (PBR) apartments, making the long-term rental supply inherently more fragile.

In short, while there has been a slight reprieve in rental costs due to supply – this trend might be short lived. With few PBR’s being constructed, and the possibility of condo’s reverting to owner occupied use, we may well see rental shortages and increasing rents during the next economic upturn.

Unintentional Retrenchment of Perceptions

City of Toronto and Federal policy documents often conflate rental housing with affordability and homelessness. The HousingTO 2020–2030 plan, for example, sets a target of 40,000 new affordable rental units (20% of which must be deeply “rent-geared-to-income” or supportive for homeless people) by 2030. In Council reports on new rental incentives, staff explicitly emphasize providing “homes affordable for residents in greatest need, including rent-geared-to-income and supportive homes for people experiencing homelessness.” Similarly, the City’s equity statements for rental programs stress serving “vulnerable and marginalized” groups via new affordable rentals. This emphasis on affordability and social housing within rental policy signals to the public that rental supply is primarily an issue of low-income housing. In practice, the word “rental” in City planning is often framed as part of solving homelessness or affordability crises. As one City of Toronto document, Perspective on the Rental Housing Roundtable notes, Toronto’s rental targets focus on “affordable rental” and “supportive housing” metrics rather than standard market rentals. The paper indicates that Toronto, in fact, is facing two housing crises – one in which rising rents have made it increasingly unaffordable for middle income earners to live in the city; and a second crisis of affordable and supportive housing for the homeless or who are experiencing family, physical, mental health and addiction struggles. The paper argues that these intersecting, but separate crises require different policy solutions, but too often in Toronto, they are treated as the same issue.

Renting Normalization in Other Cities

In most other global peer cities, long-term renting is far more normalized across all age and income groups. With home prices so steep, even middle-class professionals often rent for decades. There is less stigma because renting is simply the majority experience. In NYC a clear majority rent their homes, including many affluent households. London similarly has a huge rental sector (especially private rentals and also council housing), making renting a common and accepted living arrangement for life. Vienna and Berlin takes this even further, with most residents renting, and there is traditionally no assumption that one must buy a home. Renting is a standard, socially accepted tenure even for families and higher-income earners. Culturally, Germans have not treated homeownership as a status symbol in the way North Americans or the British often do, and strong tenant rights make lifetime renting secure.

Class and Status Views

The result of these norms is that Toronto’s renters may face more of a class/status perception gap than renters in NYC, Paris, London, or Berlin. In Toronto, a common attitude has been that renting is what you do in your 20s or when you “can’t afford a house yet,” implying that success means eventually buying a property. Homeownership is seen as a milestone of adulthood and a source of pride for many Canadians. By contrast, in cities like New York, there isn’t the same presumption that a successful 40-year-old must own a home; plenty of well-to-do New Yorkers rent by choice or necessity, and it’s not automatically viewed as a lower status. Berlin’s renters span all classes, so there is little social stigma attached to not owning – it’s entirely normal for even high-earning professionals or seniors to rent their whole lives. That said, as housing affordability challenges persist in the GTA, Canadians are slowly questioning the old narrative – The Walrus (2025) recently asked, “Many Canadians will never own a home. Does it matter?”, noting that renting is becoming a permanent reality for more people in Toronto and Vancouver. In summary, Toronto’s culture is still catching up to the idea of renting as a respectable, and long-term choice. Yet, the public narrative often lags behind these nuances: it paints a picture of an impossible rental market, without acknowledging that Montreal remains a much less expensive alternative within Canada, or that Toronto is not the worst-case scenario globally. Nevertheless, Toronto’s renters do spend a very large share of income on housing on average, and many are justifiably anxious about affordability and stability.

Crucially, beyond the numbers lies the cultural narrative. In Toronto, renting has historically been viewed as a stepping stone, overshadowed by a strong pro-ownership ideology. This contrasts with cities where renting is a normalized, even predominant way of life. Such perceptions influence policy and personal decisions: a society that valorizes ownership may invest less in tenant protections or rental supply. Combined with a market that treats housing as an investment commodity, the result in Toronto has been high costs and a sense of rental precarity. Shifting this dynamic – by learning from cities where renting is ordinary and by rebalancing housing toward its purpose as a home – will be key to improving long-term affordability and the renter experience. In sum, while Toronto’s renting situation is not uniquely dire when weighed against other cities, addressing the affordability challenge will require both continued supply growth and a cultural-policy pivot away from viewing housing chiefly as an investment or as the primary solution to homelessness.

Affordability is Important to a High Functioning Labour Market

Affordable rental housing is a foundation for robust labour supply. Studies show that without ample rental options, workers are forced to migrate to cheaper areas or become cost burdened. In turn, employers cannot draw on a full talent pool. For example, if nurses, teachers or tradespeople can’t afford to live in Toronto, companies and institutions lose skilled staff or even relocate. Economic analyses confirm that ample housing supply is linked to productivity and growth, places with severe shortages “limit labour mobility” and struggle to attract firms. In practice, affordable rentals enable broader labour participation: younger and lower-income workers (who are more likely to rent) can take jobs in the city without untenable housing costs.

Moving Forward

Rather than viewing renters as primarily a temporary or lower-income group, Toronto must fundamentally rethink how it values rental housing and the people who rely on it. Nearly half of Toronto’s households are renters representing a cross-section of workers, families, seniors, and newcomers who keep the city running. In global cities like Berlin, Vienna, New York, and London, renting is normalized across all income levels and life stages; it is not seen as a failure to own, but as a legitimate and often preferred long-term option. Toronto, by contrast, still carries a cultural narrative that equates renting with transience or financial inadequacy, a view that no longer aligns with the city’s economic or demographic realities. As housing prices have surged out of reach for much of the population, renting has become not just a stepping stone, but a permanent and necessary part of urban life.

But Toronto’s rental market cannot meet this challenge without serious and sustained policy support. Over the past 24 months, the number of construction jobs in Toronto has declined by more than 8%, and the number of job postings in the housing construction sector has plummeted by 80%, a clear warning sign that private-sector investment is stalling. Developers are pulling back from purpose-built rental projects due to rising uncertainty, costs, regulatory complexity, and competition from condominium units. If the city wants to ensure stable long-term rental supply, it must act decisively: expedite approvals, reduce fees for purpose-built rentals, offer property tax relief, and treat rental housing as a priority class of development. The City of Toronto has taken a few steps towards this. Let’s continue to unleash the market, not through deregulation, but through smart policy that de-risks rental construction and enables it to scale. Toronto cannot afford to wait. The foundation of its economy, young construction workers who were promised bright futures and high earnings, and livability depends on getting this right.

Appendix: Rental Market Affordability in 16 Global Cities

Housing affordability is typically assessed by the share of income spent on rent, with anything above about 30% considered a high-cost burden. Below, we examine 16 major cities, detailing each city’s rental affordability (percent of income spent on rent), renter demographics (percent of population renting), relevant government policies (like rent control), and unique challenges or benefits for renters.

Despite being one of the world’s largest cities, Tokyo manages to maintain a more balanced rent affordability through abundant housing supply. Roughly 55% of Tokyo’s residents rent their homes (homeownership is lower in the city than in Japan overall). The typical rent in Tokyo is much lower relative to income than in global cities like London or New York – one analysis noted that the median Japanese tenant spends only about 20% of their disposable income on rent (for central Tokyo apartments the ratio might be higher, but still generally more attainable than in Western financial capitals.) Japan does not have rent control; instead, pro-development policies in Tokyo have led to a high volume of housing construction, which helps keep rent increases modest. Government regulations are light, aside from standard tenant protections and certain rental contract customs. A unique feature of renting in Tokyo is the prevalence of small, efficient apartments and the tradition of “key money” (an upfront gift payment to the landlord) along with deposits and agency fees, which can make initial move-in costs high. On the plus side, renters benefit from a stable or gradually adjusting rent market – rent in Tokyo has risen only slowly over time due to the continuous addition of new units. In summary, Tokyo offers renters relatively reasonable affordability and choice by international standards, illustrating how high housing supply can mitigate rent burdens in a mega-city.

Rental Affordability – Affordable

55% of population rents

Vienna stands out for affordable rents and a dominant renting culture. Renters in Vienna spend roughly 25–30% of their income on housing, one of the lowest burdens among global cities. Around 80% of Vienna’s population lives in rental housing, thanks in large part to the city’s extensive social housing program. The government owns or subsidizes well over half of the housing stock, with rents often capped at 25% of tenants’ earnings. This strong public intervention yields many benefits: Vienna’s renters enjoy stable, long-term leases and comparatively low rents. A unique challenge, however, is that demand for subsidized apartments can lead to waiting lists, and the private rental sector (though regulated) has seen some recent rent increases as the city grows.

Rental Affordability – Affordable

80% of population rents

Seattle’s rental market benefits from high incomes, keeping rent affordability better than in many peer cities. The average Seattle renter spends roughly 25–30% of their income on rent, which is relatively manageable compared to Vancouver. A majority of Seattle residents (around 58%) are renters, reflecting the city’s influx of young professionals in the tech industry. Washington State law prohibits local rent control (a ban in place since 1981), so there are no caps on rent increases. Instead, affordability has hinged on Seattle’s robust job market raising incomes. Unique challenges include rapid growth and limited housing supply, which have driven up rents in recent years, but the city has responded with tenant protections (such as eviction prevention measures) and increased development to accommodate its growing renter population.

Rental Affordability – Affordable

58% of population rents

Montreal is known for its relatively affordable rents and a high proportion of renters. Rent takes up about 28–29% of the average income in Montreal, below the 30% affordability threshold and lower than many other big cities. The city proper has about 63% of its population renting homes, the highest share in Canada. Quebec’s housing policies provide some informal rent control: the provincial rental board issues annual rent increase guidelines, and tenants can legally refuse large increases and have the board set a fair rent. This framework, along with tenant-friendly rules (e.g. no security deposits), helps keep Montreal’s rental market stable. Renters benefit from the city’s abundant older housing stock and traditionally modest rents, though challenges are emerging as low vacancy rates and rising demand put pressure on prices. Overall, Montreal remains more affordable for renters than Toronto or Vancouver, but continued attention is needed to preserve that advantage.

Rental Affordability – Affordable

63% of population rents

Stockholm’s rental sector is tightly controlled but difficult to access. On average, renters spend about 30% of their income on rent in Stockholm, near the typical affordability cutoff. Only around 43% of Stockholm’s population rent their housing (a minority, unlike most other cities on this list), partly because Sweden’s strict rent control system has led to few private developments, causing many to seek homeownership or cooperative apartments instead. The government, through tenant unions, regulates rent levels which keeps rents relatively low – but the downside is extremely long waiting lists for regulated apartments. In Stockholm, the queue for a rent-controlled apartment can stretch 10–20 years, and many tenants hold onto these flats for life. This means newcomers often resort to sublets or the small unregulated segment at much higher prices. The benefit for those who do get a contract is strong tenant security and affordable rent; the challenge is the scarcity of available rentals, a direct outcome of decades of aggressive price regulation.

Rental Affordability – Slightly Affordable

43% of population rents

Singapore presents a unique case where the statistics on renting reflect its distinct housing system. According to the provided data, about 85% of Singapore’s population lives in rental housing, yet Singapore also boasts a homeownership rate of around 90% among resident households. This apparent contradiction is explained by Singapore’s public housing scheme: most citizens purchase subsidized Housing & Development Board (HDB) flats on long-term leases, which counts as homeownership. The high “renting” figure likely comes from the large number of non-citizen residents and those in transitional arrangements who rent, as well as the fact that technically HDB lessees do not own land. In terms of affordability, Singapore’s housing costs are kept in check for locals – the government ensures public housing is affordable, often aiming for housing costs around 30% of income. There is no traditional rent control; instead, the government itself is the provider of affordable housing. Unique benefits include a very stable housing market for citizens (with generous grants and fixed mortgage rates), while challenges exist for expatriates and others in the private rental market, where rents can be quite high. Overall, Singapore’s strong state intervention has made home ownership (through public rentals) the norm, leaving the private rental market as a smaller, albeit pricey, segment mostly for foreigners and high-income locals.

Rental Affordability – Slightly Affordable

Renter Demographics = 85% of population rents

Chicago has a large renter population and relatively moderate rents compared to other U.S. cities. Approximately 58% of Chicago’s population lives in rental housing (the city shifted to a renter-majority in the 2010s). The average Chicago renter spends about 38% of their income on rent, which is above the recommended 30% threshold but lower than the burden in places like Los Angeles or New York. Unlike some cities, Chicago has no rent control, Illinois state law has prohibited rent control since 1997. Government efforts instead focus on affordable housing construction and vouchers, as well as tenant rights ordinances, but rents are set by the market. A unique aspect of Chicago is the wide variation across neighborhoods: in some South or West Side areas rents are quite affordable, whereas downtown and North Side rents have risen steeply. The city’s benefit to renters is a relatively large supply of housing (keeping rents more manageable)while challenges include pockets of housing insecurity and an aging rental stock in need of maintenance. Overall, Chicago offers more affordability than many peer cities, though lower-income renters still face cost pressures absent any rent caps.

Rental Affordability – Slightly Unaffordable

58% of population rents

Berlin is often cited as a “city of renters,” with about 84% of residents renting their homes – one of the highest renter populations in the world. Berlin’s renters traditionally had relatively low rents, but in recent years affordability has worsened: the average rent now claims roughly 40–43% of a renter’s income (higher than in most German cities). The government has a history of intervention in the rental market. Germany’s federal rent control law (Mietpreisbremse) limits rent increases for new leases in tense markets (landlords generally can’t charge more than 10% above the local average rent for similar units). Berlin even tried to impose a citywide rent freeze in 2020, though it was struck down by the courts. In addition, roughly half of Berlin’s rental apartments are owned by municipal or cooperative landlords, and tenant protections (like indefinite leases and eviction restrictions) are strong. The unique challenge in Berlin is that demand now far outstrips supply, causing sharp rent hikes despite the controls – advertised rents jumped over 20% in 2023 alone. This has led to grassroots movements, including a recent referendum to potentially expropriate large corporate landlords and turn their units into social housing. In summary, Berlin’s renter-majority enjoys robust legal protections and historically low rents, but the city is currently grappling with a severe housing crunch and rapidly rising rents on the open market.

Rental Affordability – Slightly Unaffordable

84% of population rents

Paris is a high-cost city for renters, with about 65% of Parisians renting their homes and spending on average around 45–50% of their income on rent (indicative of a very heavy burden). To combat runaway rents, the French government reintroduced rent control in Paris in 2019 (“encadrement des loyers”), which sets a reference rent and limits rents to within 20% above that benchmark for new leases. Compliance is not universal, but the policy has helped moderate rent increases somewhat. Paris also has a significant social housing sector: roughly one-quarter of residents live in publicly subsidized housing, up from only 13% in the late 1990s. This expansion of social housing is meant to keep middle and low-income families in the city. Unique challenges for Paris renters include very small apartments and intense competition for housing in desirable arrondissements. Benefits come from strong tenant rights under French law (standard leases are typically 3 years and difficult for landlords to break) and the city’s investment in affordable housing. Even so, Paris remains extremely expensive: locals often need flatmates or long commutes to cope, and many are effectively “priced out” of central Paris despite the government’s interventions.

Rental Affordability – Slightly Unaffordable

65% of population rents

London is one of the most expensive rental markets globally, where affordability is a serious issue. Approximately 52% of London’s households rent their home (making renters just over half the population). By some estimates, the average rent for a one-bedroom flat in London is equivalent to almost half of a median worker’s gross pay (around 46%) and in many central boroughs it can be far higher – meaning many renters spend well above 50% of their income on rent. In fact, without flatmates or dual incomes, renting in London can be nearly impossible on a normal salary. The UK has no rent control for private rentals; landlords can generally charge what the market bears, subject only to modest limitations (e.g. caps on rent increases within a fixed-term tenancy and notice period requirements). The government’s role has instead been through providing social housing and housing benefits. About 23–25% of London’s housing stock is social housing (council or housing association homes) which offers below-market rents to those who secure a unit. London’s Mayor and UK Parliament have debated stronger tenant protections – such as ending “no-fault” evictions and possibly implementing rent freezes – but as of now the market remains largely deregulated. Unique challenges for London renters include short-term tenancies (commonly 12 months), the need for substantial upfront payments (deposits and rent in advance), and competition from international renters and investors. The upside is that London’s economy offers high wages for some, and its extensive public transport allows living further out to find cheaper rent. Still, compared to other cities, London’s rental affordability is among the worst, and the city is actively seeking solutions to address the stress on its renting population.

Rental Affordability – Slightly Unaffordable

52% of population rents

Boston is another expensive market with a high share of renters. About 68% of Boston’s population lives in rental housing, and the typical renter household spends roughly half of its income on rent (around 50% on average), indicating serious affordability pressures. Unlike New York or San Francisco, Boston currently has no rent control – Massachusetts banned rent control statewide in the 1990s. However, there is active discussion to reinstate rent stabilization: in 2023, Boston’s city government advanced a proposal to cap annual rent increases at around 10%, though it requires state approval. In the absence of rent caps, the city relies on affordable housing requirements for new developments and housing voucher programs. A unique aspect of Boston’s rental scene is the influence of universities and colleges. The large student population drives seasonal demand and can push up rents in student-heavy neighborhoods. On the other hand, Boston’s strong knowledge economy means many renters have relatively high incomes, which can partly offset the high rents. The city’s challenge moving forward is balancing growth with affordability – Boston is exploring new tenant protections and zoning reforms to expand housing supply, aiming to relieve the rent burdens on its diverse renter community.

Rental Affordability – Slightly Unaffordable

68% of population rents

Vancouver consistently ranks as Canada’s least affordable cities for renters. The average renter in the City of Vancouver spends over half their income on rent. About 54% of Vancouver’s population rents their home, a figure that has been inching upward as housing prices make ownership difficult. The government of British Columbia maintains rent control for existing tenancies: annual rent increase guidelines (tied to inflation) typically limit raises (for example, the cap was 2% in 2023). This means sitting tenants have some protection, although when a unit turns over to a new renter, the landlord can reset to market rent. Vancouver’s renters face unique challenges, including near-zero vacancy rates (around 1% or lower in recent years) and competition from investors in the housing market. The city has taken measures like taxing empty homes and limiting short-term rentals to push more units into the rental supply. A benefit for renters is that many newer high-rise apartments have been built, adding supply, but these units often target the luxury market. In sum, despite provincial rent controls, Vancouver’s rental affordability remains very poor – a reflection of the city’s overall housing crisis – and tenants often must allocate an exorbitant portion of income to secure accommodation.

Rental Affordability – Not Affordable

Renter Demographics = 54% population in rental housing

Los Angeles has one of the least affordable rental markets in the U.S., with renters commonly paying over half their income toward housing. In L.A. city, the median rent is about 50–52% of household income on average, and across L.A. County over 29% of all households are severely rent-burdened, spending more than 50% of income on rent. Around 68% of Angelenos rent their homes (54% in the broader county), reflecting the high cost of homeownership in Southern California. To protect renters, California enacted a statewide rent cap in 2019 (the Tenant Protection Act) capping most annual rent increases at 5% plus inflation (up to 10% maximum). Moreover, the City of Los Angeles has had its own rent stabilization ordinance for decades, limiting rent hikes on older buildings. These policies provide some relief, but unique challenges remain: L.A.’s housing supply has not kept up with demand, leading to low vacancy rates, and many lower-income renters face overcrowding or long commutes from distant cheaper areas. The benefit for L.A. renters is that tenant protections (including eviction controls) were strengthened during the pandemic, yet the city continues to struggle with a homelessness crisis tied to the extreme rent burdens.

Rental Affordability – Not Affordable

68% population in rental housing

Seoul’s rental market is characterized by unique leasing systems and lately, mounting affordability concerns. An estimated 60% of Seoul’s population lives in rental housing (when including all forms of leases). Rent affordability on a monthly basis can be extremely poor for those who rent conventionally – by one measure, Seoul renters might spend on average up to 79% of their income on rent, which signals an acute affordability crisis. However, South Korea’s traditional jeonse system complicates this picture. Under jeonse, tenants pay a large lump-sum deposit (often 50–80% of the property’s value) to the landlord for the duration of the lease instead of monthly rent. Many Seoul residents still use jeonse, meaning they have no monthly rent (hence a low rent-to-income ratio for those households), and they get their deposit back at lease end – effectively an alternative route to reduce housing costs if one can afford the upfront sum. In recent years, as housing prices soared and interest rates changed, jeonse has become less accessible, pushing more people into monthly rental agreements. The government does not impose rent control in Seoul’s private market, but it has expanded public rental housing and provides rent subsidies for low-income families. Unique challenges include jeonse deposit fraud cases and the shift toward monthly rentals increasing cost burdens. On the other hand, renters benefit from the security of jeonse (for those who can manage it) and long lease terms. In summary, Seoul offers a mixed picture: a historically innovative rental model that kept costs low is under strain, and many renters now face very high monthly rents, prompting the government to seek new measures to ensure affordability.

Rental Affordability – Not Affordable

60% population in rental housing

New York City is famously expensive for renters, though a mix of policies slightly blunts the impact for some. About 69–72% of New York City households are renters. On the open market, rents have reached record highs – the citywide median asking rent is around $3,500 per month, which would require an income of $140,000 to avoid being rent-burdened (30% of income). In other words, market rents in NYC often consume well above 50% of a typical household’s income, and the provided data even suggests an average rent-to-income ratio over 100%. However, New York has extensive rent regulation that helps millions of tenants. Roughly half of rental apartments are rent-regulated (rent-stabilized), which means rent increases are capped by a city board each year and tenants have the right to lease renewals. This keeps many long-term renters paying below-market rates, tempering the overall affordability crisis. The city also has a large public housing system (nearly 170,000 units operated by NYCHA) and issues tens of thousands of Section 8 housing vouchers for private units. The unique situation in NYC is that despite extraordinarily high housing costs, these interventions allow a range of income groups to remain in the city, but those entering the market fresh face steep rents. Benefits for renters include strong legal protections (New York recently guaranteed free legal counsel for low-income tenants facing eviction, for example) and a relatively robust supply of apartments (including new high-rises). Still, New York’s housing demand outpaces supply in desirable areas, and homelessness and housing insecurity remain pressing problems. Compared to Toronto, New York’s rent burdens are significantly higher and a larger share of its populace rents, highlighting the intense pressure on housing in the Big Apple.

Rental Affordability – Not Affordable

69% – 72% population in rental housing

Summary

Rather than seeing renters as a temporary or lower-income group, Toronto needs a reset in how it thinks about rental housing and the people who live in it. In many global cities, renting is a permanent, normalized, and respected housing choice—one that accommodates families, professionals, seniors, and newcomers alike. If Toronto aspires to be truly world-class, it must embrace a housing strategy that reflects the full spectrum of its residents’ needs. That means offering a broad array of stable, high-quality, and affordable rental options—not as a fallback, but as a foundation of an inclusive and economically competitive city.

Striking the Balance

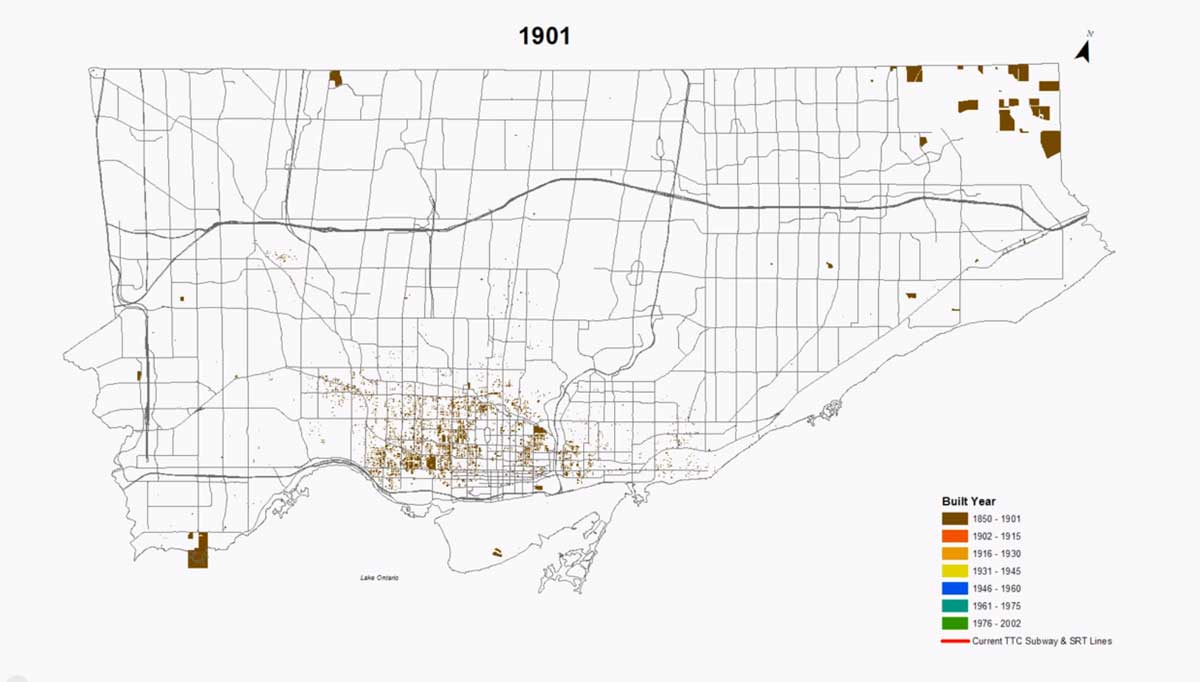

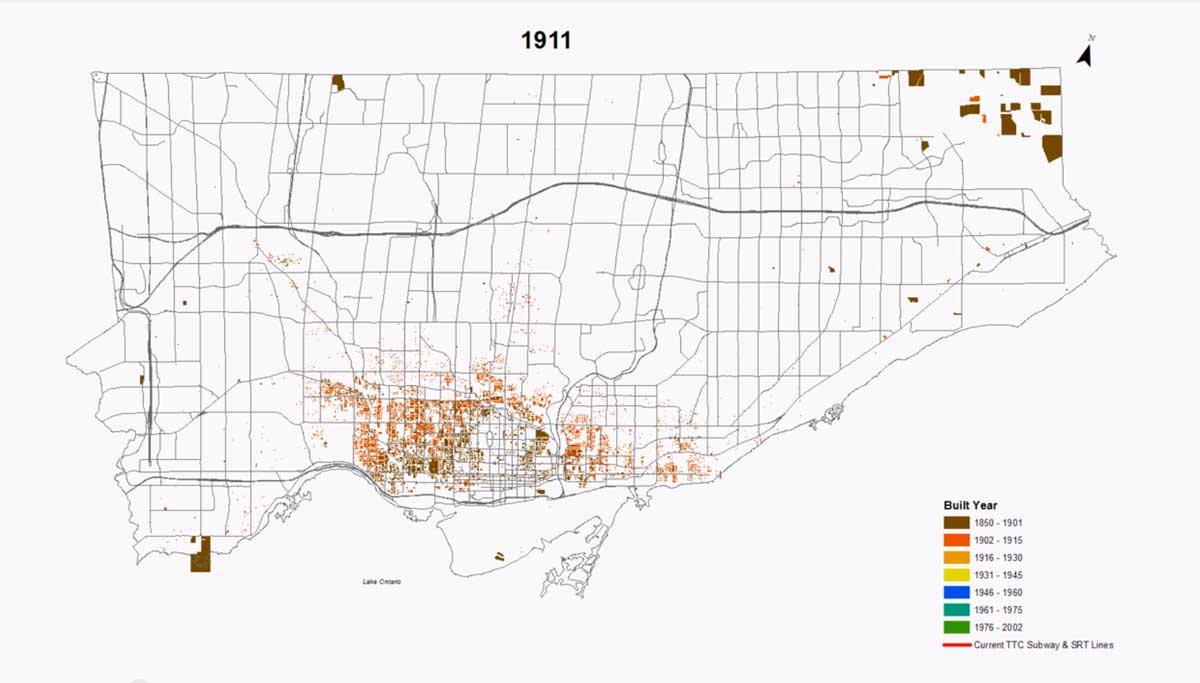

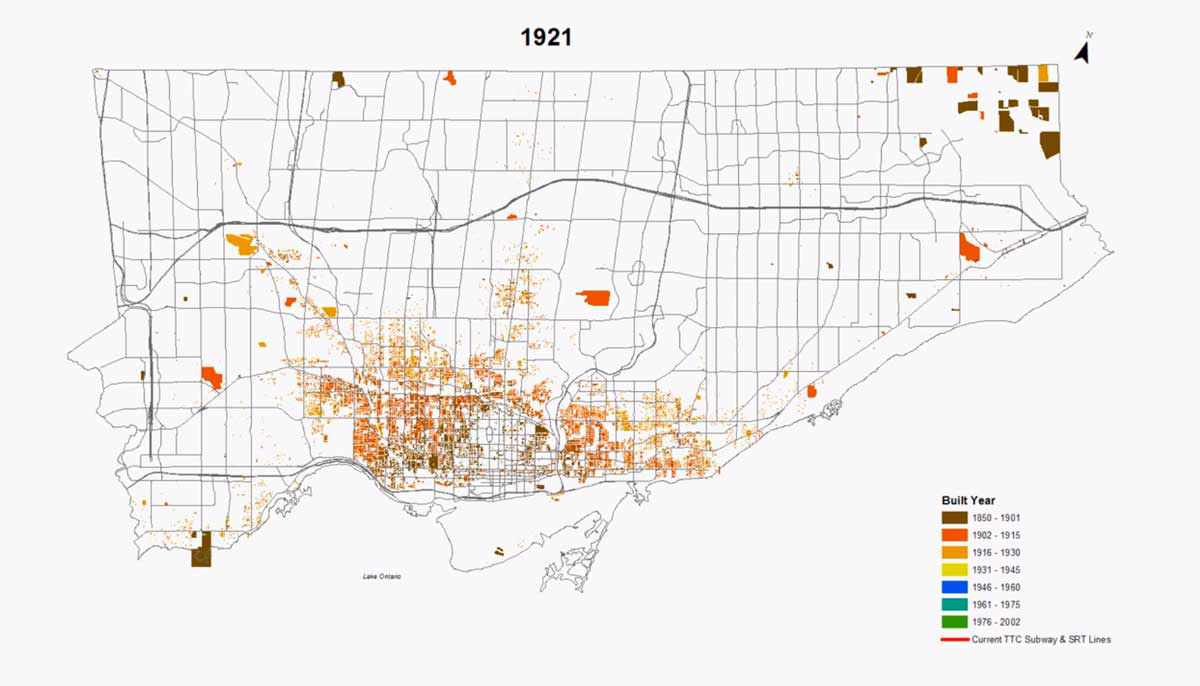

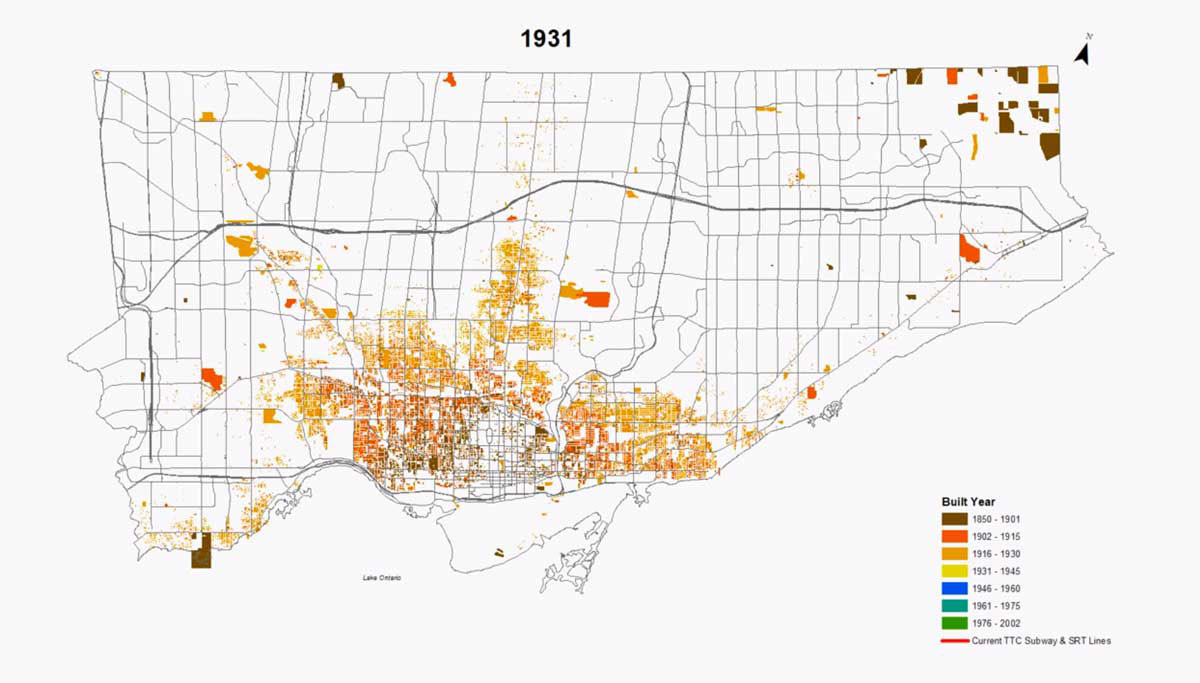

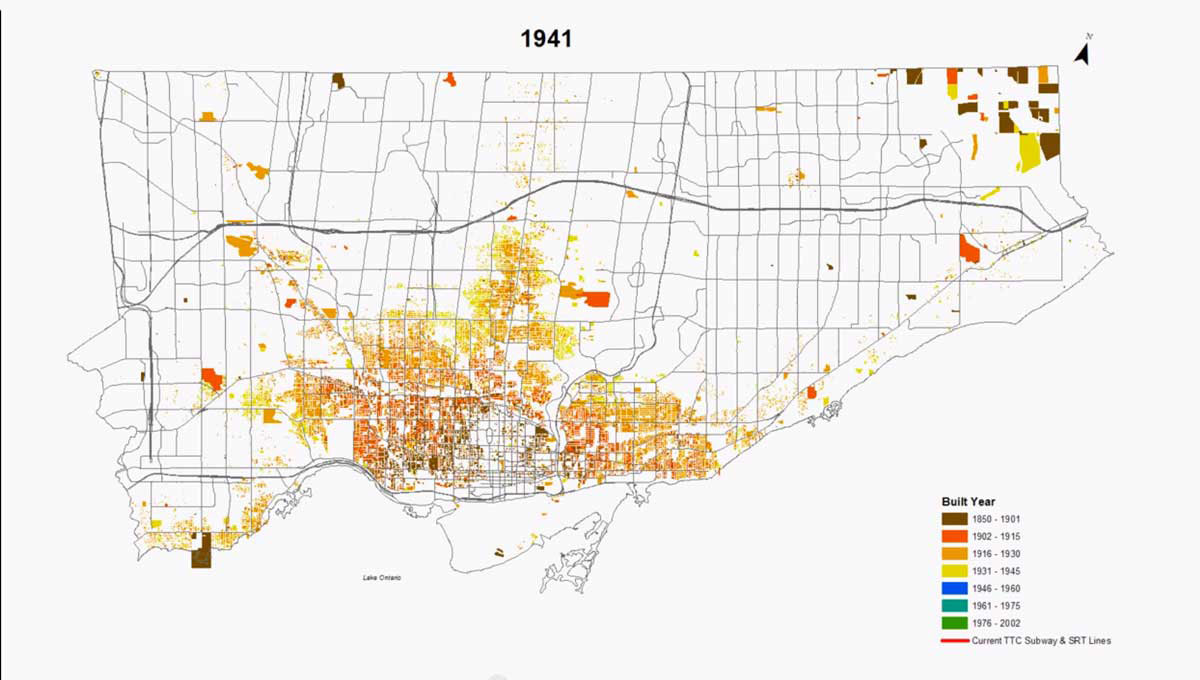

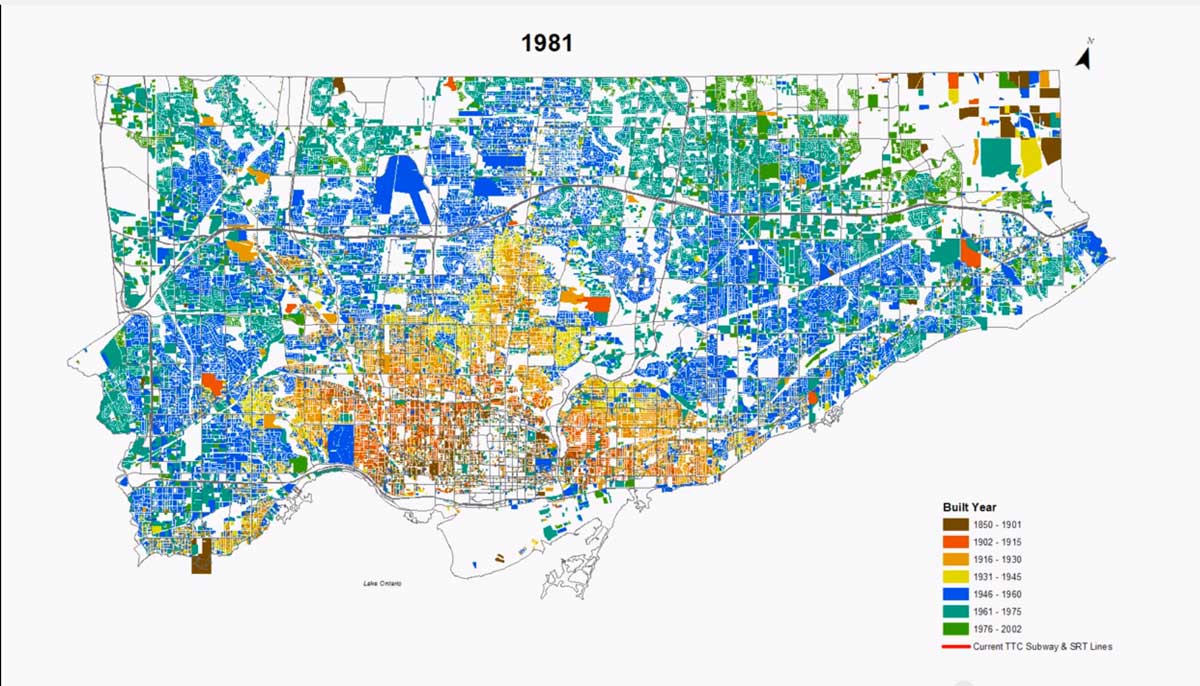

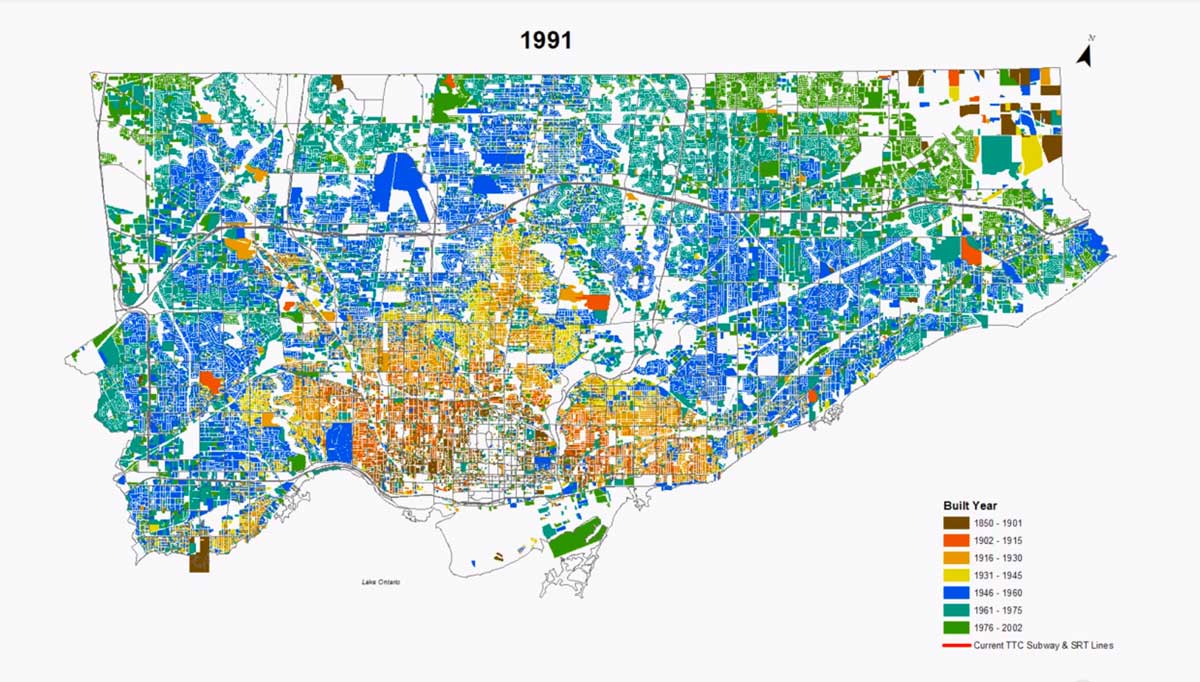

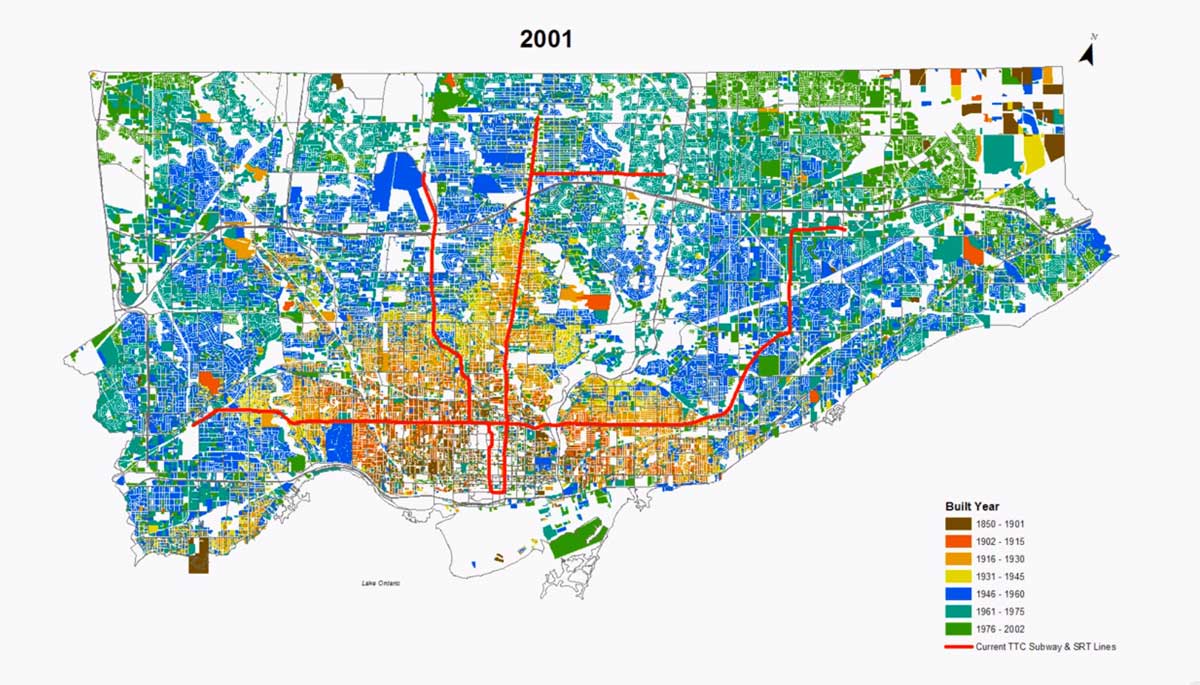

In the first article of this series, we explored how housing in Toronto transitioned from being a place to live into a high-stakes investment vehicle, reshaping affordability and accessibility to housing for residents. Building on that foundation, this article examines the ongoing challenge of balancing housing availability, construction labour supply, and urban space constraints. As Toronto has grown into a major metropolitan hub, achieving this balance has become increasingly difficult. The city has faced periods of rapid expansion followed by downturns, creating a volatile cycle that impacts both residents and workers. From the 1920s suburban expansion to modern high-rise booms, Toronto’s housing industry has continuously evolved, but the recurring challenge of boom-and-bust cycles in construction has significant implications for long-term urban planning and workforce stability.

1920s: The Birth of Suburban Toronto

The 1920s ushered in a period of early suburban expansion. With a population nearing 500,000, Toronto saw the rise of single-family detached homes in areas such as The Annex, High Park, and East York. Influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, homes featured brick exteriors, pitched roofs, and front porches. Streetcar expansion fueled suburban growth, while early zoning laws promoted low-density development. Housing prices ranged from $3,000 to $5,000, reflecting a booming economy and increasing homeownership aspirations.

Estimated Construction Workforce: Around 5,000 workers, predominantly male, of British and European descent. Wages ranged from $0.50 to $1.00 per hour, with many working as day labourers in precarious conditions. Most workers had little formal education, with many having only primary schooling or informal apprenticeships. Construction remained largely unregulated, and unionization efforts were minimal at this stage.

1930s: Economic Struggles and Modest Housing

The Great Depression significantly slowed housing development. Population growth continued, reaching about 650,000, but economic hardship meant that smaller, more affordable bungalows and duplexes became prevalent, especially in Scarborough and North York. Construction was cost-conscious, using brick and wood-frame materials, with homes costing $2,500-$4,000. Limited financial support for homebuyers and stricter lending policies further constrained growth.

Estimated Construction Workforce: Around 3,000 workers, largely European immigrants and local labourers. Wages dropped to $0.25 to $0.50 per hour, and job security was low. Education levels remained low, with many workers learning on the job. Early trade union movements began to form, but formal labour protections were still in their infancy.

1940s: Post-War Expansion and Victory Homes

Following World War II, Toronto’s population reached 700,000, and returning soldiers fueled a demand for affordable housing. Government-backed initiatives led to the construction of Victory Houses—small, functional bungalows in areas like Don Mills and East York. Prefabricated materials and simple designs enabled mass production, with homes costing between $5,000 and $8,000. Wartime material shortages limited architectural diversity, but the city saw its first major suburban expansion.

Estimated Construction Workforce: Around 10,000 workers, including returning veterans, British, Italian, and Eastern European immigrants. Wages improved to about $1.00 to $1.50 per hour. Many workers had limited formal education but were trained through military service or informal apprenticeships. Construction unions began gaining traction, advocating for better wages and working conditions.

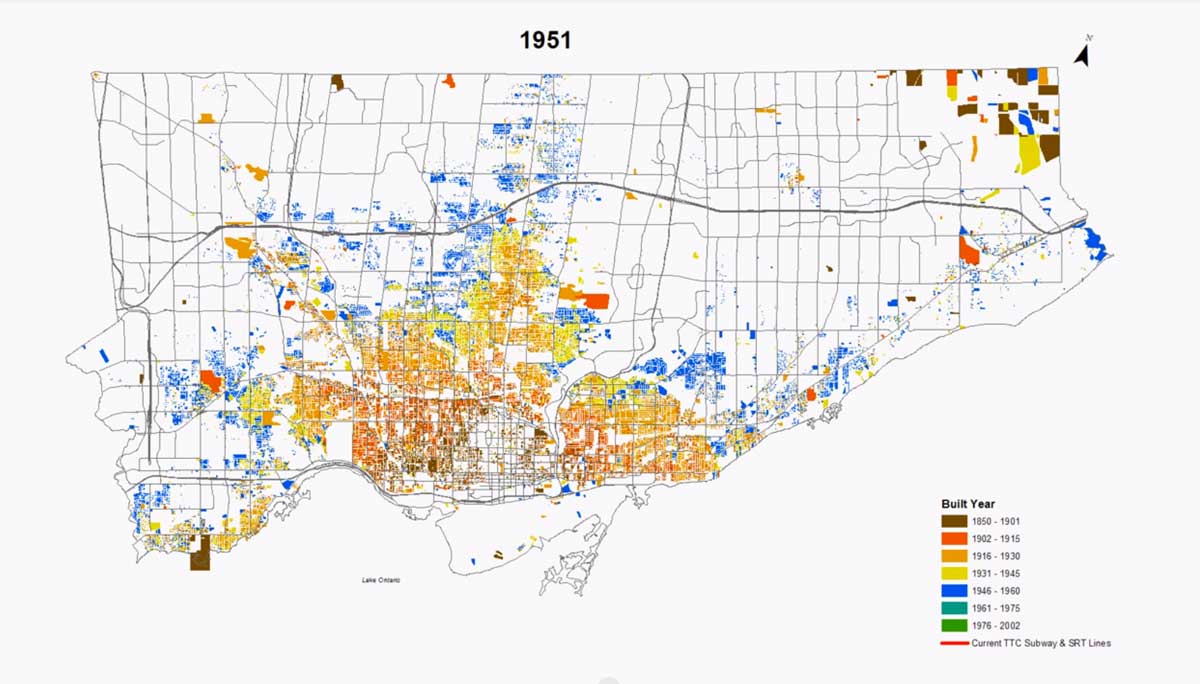

1950s: The Rise of Car-Oriented Suburbs

Toronto surpassed 1 million residents as post-war prosperity drove suburban expansion. Ranch-style bungalows and split-level homes dominated new developments in Etobicoke, North York, and Scarborough. Brick veneer and asphalt-shingle construction became common. The city’s expanding highway network, including the Don Valley Parkway, facilitated suburban commuting. Homes cost between $10,000 and $15,000, supported by accessible mortgages and a growing middle class.

Estimated Construction Workforce: Around 20,000 workers, with an increasing number of Italian, Portuguese, and Eastern European immigrants. Wages ranged from $1.50 to $2.50 per hour. Many workers had limited formal schooling, but trade unions strengthened, offering apprenticeship programs and vocational training.

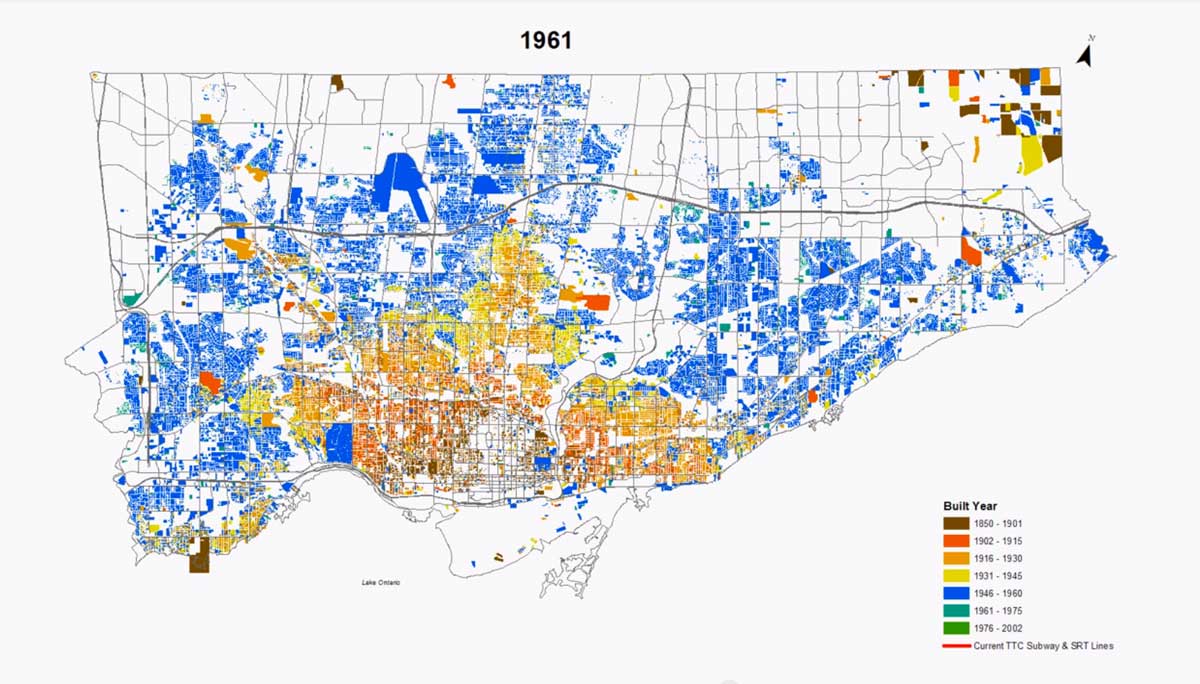

1960s: The High-Rise Boom

With a population of 1.5 million, Toronto experienced rapid urbanization. High-rise apartments and suburban back-split homes emerged, particularly in Flemingdon Park and Thorncliffe Park. Concrete high-rises reshaped the skyline as zoning changes encouraged densification. Homes cost $15,000-$25,000, but rising immigration and limited affordable housing intensified demand.

Estimated Construction Workforce: Around 30,000 workers, increasingly diverse with more Caribbean, Asian, and Southern European immigrants. Wages reached $3.00 to $4.50 per hour. Many workers had vocational training or high school education. Construction unions played a major role in securing safety standards and wage protections.

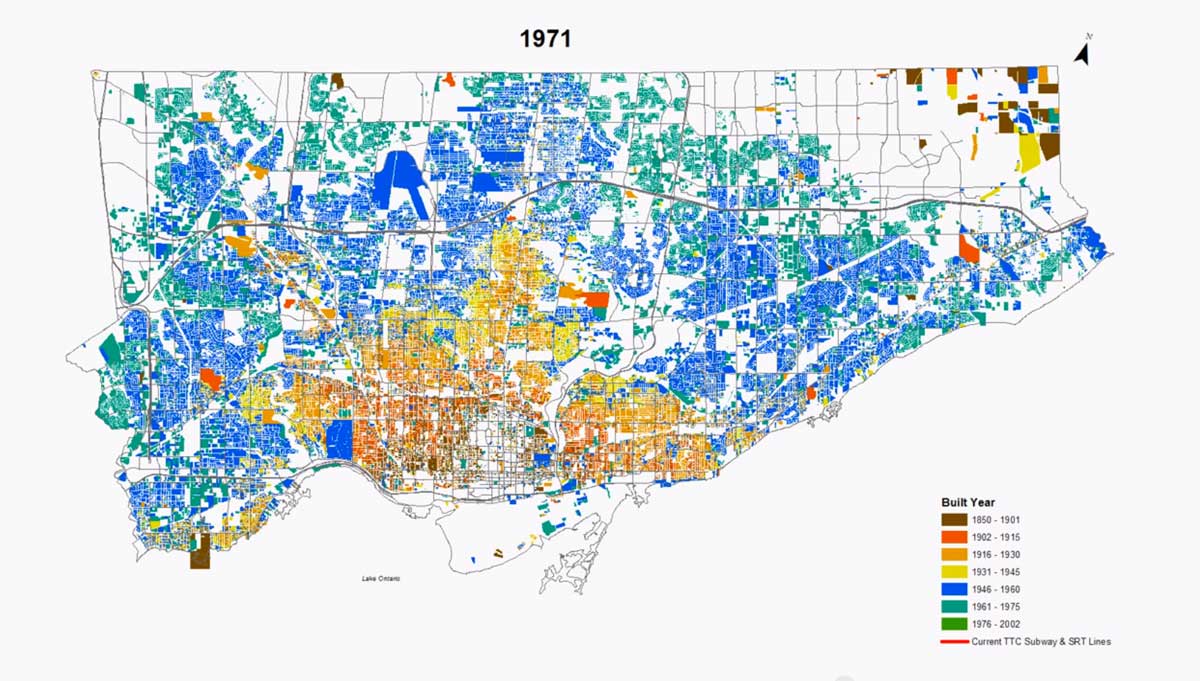

1970s: Condominium Legislation and Intensification

The Condominium Act of 1967 sparked a condo boom, making homeownership more accessible. The population of Toronto Region exceeded 2 million, with significant development in North York and Scarborough. Townhouses and high-rises dominated new construction, with materials shifting toward concrete and energy-efficient designs. Housing prices ranged from $30,000 to $50,000, influenced by economic inflation and evolving mortgage policies.

Estimated Construction Workforce: Around 40,000 workers, with a growing proportion of South Asian and Middle Eastern immigrants. Wages increased to about $5.00 to $6.50 per hour. Many workers attended trade schools or participated in union apprenticeship programs.

1980s-Present: Unionization, Investment, and Affordability Crisis

Toronto’s housing market exploded in the 2000s, with prices soaring to $400,000-$600,000. High-rise condos, mixed-use developments, and luxury homes proliferated, particularly in Liberty Village and downtown. By the 2010s, detached home prices exceeded $1 million, and affordability concerns dominated policy discussions. High-rise condos dominated new construction, while laneway homes and micro-apartments emerged as alternatives.

Estimated Construction Workforce: Over 100,000 workers today, representing a highly diverse mix of backgrounds, including significant South Asian, East Asian, Middle Eastern, and Caribbean populations. Wages now range from $20.00 to $50.00 per hour, depending on skill level and specialization. Most workers have formal vocational training, trade certifications, or union apprenticeships. Unionization is widespread, ensuring labour protections, benefits, and standardized training programs.

Finding the Balance

Toronto’s housing evolution reflects shifting economic, social, and policy dynamics. From early suburban expansion to high-rise densification, affordability has remained a persistent challenge. However, beyond affordability, the volatility of the construction sector itself presents long-term risks. The city’s housing industry has historically experienced dramatic swings in activity, with construction booming during periods of economic growth only to slow sharply during downturns. This was evident in the 1990s and is once again becoming a concern today as housing construction declines. As a result, workers in the construction industry face periods of job scarcity, while policymakers struggle to align housing supply with demand without creating surplus labour during slowdowns.

One of the most pressing issues contributing to Toronto’s housing shortage has been a lack of skilled construction workers. When demand for new housing soared, the availability of labour struggled to keep pace. This shortfall has been exacerbated by an aging workforce, a decline in young Canadians entering the trades, and delays in training new workers. In response, federal and provincial governments have implemented training programs aimed at attracting more workers to the skilled trades. Initiatives such as the Ontario Youth Apprenticeship Program (OYAP) and financial incentives for apprenticeships have sought to increase local participation in the construction sector. However, during downturns, these same workers may struggle to find employment, leading to instability in the industry and the overall economy.

Additionally, immigration policy has played a crucial role in addressing the labour gap. In recent years, Canada has expanded pathways for skilled trades workers to immigrate through programs such as the Federal Skilled Trades Program and the Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program (OINP). These policies have helped recruit construction workers from around the world, ensuring that Toronto’s building sector remains active despite local labour shortages. However, challenges remain, including credential recognition and integration into the workforce, which require continued government intervention and industry collaboration. More importantly, without measures to stabilize the industry, periods of rapid expansion followed by construction slowdowns could leave new workers facing long spells of unemployment, reducing the overall appeal of the trades as a career path.

Looking ahead to the next article for Toronto at Home, our ability to meet housing needs will depend on sustained efforts to attract, train, and retain skilled workers while also addressing the cyclical nature of the construction industry. Without a stable and well-supported construction labour force, the city will continue to experience bottlenecks in new developments and exacerbated housing shortages. A more proactive approach to workforce planning, including better forecasting of housing needs, sustained investment in training, and policies that moderate construction volatility, will be essential. Balancing housing availability, space for new development, and workforce sustainability will define Toronto’s housing future—ensuring that the city remains livable and accessible not just for residents but also for those who build it.

When a Place to Live Became an Investment

In the 1960s, a Portuguese family who had recently arrived in Toronto settled in Hillcrest Village, a quiet neighborhood just west of the city’s bustling downtown. The father, working a steady job in one of the city’s many manufacturing plants, and the mother, perhaps sewing in a factory or cleaning houses, could afford to buy a modest home on their combined wages. Back then, a house was simply a place to live, a refuge for raising children and building a life in a new country. For newcomers like them, homeownership wasn’t about wealth-building or speculation—it was about stability, community, and opportunity. Fast forward to today, and for that family, new to Canada and starting their first jobs, buying a home feels like a distant dream. The city’s housing market has transformed into one of the most expensive in the world, driven by decades of financialization, speculation, and skyrocketing demand. This shift hasn’t just left aspiring homeowners behind; it’s also rippled through the rental market, creating deep inequalities in housing access and affordability.

In the decades following World War II, Canadian housing policy reflected a national commitment to stability and prosperity. Homeownership was promoted as a cornerstone of community building and economic recovery, supported by initiatives like the National Housing Act of 1944. In cities like Toronto, working families—often recent immigrants—could afford modest homes in emerging suburban neighborhoods such as East York, West Hill, Bayview Village and Mimico, even on a single income. Housing prices remained stable, aligned with wage growth, and homes were primarily viewed as places to live, not as financial assets. The post-war housing boom, driven by accessible mortgages and affordable construction, allowed millions to achieve homeownership, forming the foundation of the Canadian middle class.

By the 1980s however, the dynamics of homeownership began to shift in response to broader economic and policy changes. Reforms led to financial deregulation, which expanded access to credit and facilitated higher levels of borrowing. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) pivoted from its original focus on affordable housing to insuring mortgage debt, enabling riskier lending practices. Toronto, as a rapidly growing global city, became increasingly attractive to foreign investors seeking safe and appreciating assets. Housing was no longer seen merely as a dwelling but as an investment vehicle; a cultural shift reinforced by public policies like tax exemptions on primary residence capital gains. Real estate began to serve dual roles: a source of shelter and a key driver of wealth accumulation.

While housing prices increased during the period of 1965 to the early 2000’s (although it is worth noting that during the first part of the 1990’s, housing prices declined), it was not until 2005 that housing prices started to dramatically shift upwards. Historically low interest rates over a sustained period made investment in houses more attractive while returns on fixed-income investments like bonds and savings accounts were far less attractive. As seen in the graph below, Toronto housing has increasingly been perceived as a low-risk, high-return investment, outperforming traditionally safer assets like bonds while avoiding the volatility of stocks. While stocks have historically provided the highest returns, their short-term fluctuations and economic sensitivity make them riskier. Bonds, once considered the safest investment, have faced challenges from inflation and interest rate fluctuations, reducing their appeal. In contrast, housing in large metropolitan areas has been increasingly viewed as a stable wealth-building asset, particularly in cities like Toronto, where prices have rapidly risen.

The current home buyer (or investor) is unlikely to remember the 1990s real estate crash, or if they do, it is considered an anomaly. In short, buyers and investors increasingly perceived housing as a secure investment that offered both stability and superior long-term returns when compared to bonds or even stocks. A cursory review of housing advertisements spanning from the early 2000’s to current times demonstrates an increased focus on housing as an investment. The proliferation of marketing content and advertising strategies are aimed at real estate investors. From the early 2000’s on, residential ads began to commonly emphasize terms like “investment property,” “ROI,” and “rental yields,” underscoring the financial advantages of housing as an investment.

Toronto has one of the lowest property tax rates in North America while imposing some of the highest development charges for housing. This combination drives up home prices, creating an environment that benefits existing homeowners while making it harder for new buyers to enter the market. Toronto’s tax rates have been comparatively low for over 40 years, contributing to higher housing costs as local and foreign investors prefer cities with lower holding costs, fueling speculation and reducing the supply of homes for end-users, ultimately pushing prices higher.

Meanwhile, a study by Altus Group Economics found that Toronto’s development charges are among the highest in North America, particularly for low-rise housing. Government-imposed charges in Toronto are, on average, three times higher per unit than in most U.S. metropolitan areas and about 1.75 times higher than in other Canadian cities. These elevated development fees increase the overall cost of housing, as developers pass these costs on to consumers. In effect, the city’s policies—whether intentional or not—disproportionately favour existing homeowners by keeping their tax burdens low while shifting the cost of growth on to future residents.

The concept of housing as an investment, combined with historically low interest rates, Toronto’s population growth (one of the fastest growing cities in North America), and restrictive zoning policies created significant pressure on Toronto’s housing supply, fueling an unprecedented surge in home prices. Between 2000 and 2023, average home prices in the city increased by over 300%, fundamentally altering the accessibility of homeownership.

The redefinition of housing as an investment has had significant spillover effects on Toronto’s rental market. Skyrocketing home prices pushed more residents into the rental market, driving average rents for a one-bedroom apartment to over $2,500 per month by 2023. This convergence of factors created a cascading effect: tenants faced higher rents, displacement through “renovictions,” and increasing housing insecurity. Purpose-built rental developments, which once played a crucial role in providing stable, affordable housing, stagnated as developers focused on more lucrative condominium projects.

And why not? Ontario’s rent control measures, first introduced in 1975, were well intentioned and designed to protect tenants from rapid rent increases as inflation hovered above 10% and with a peak of 20% in 1981. The 1986 Residential Rent Regulation Act further tightened restrictions, limiting how much landlords could charge even for new tenants. By 1992, the provincial government introduced vacancy control, preventing landlords from adjusting rents to market levels after tenants moved out. While these policies provided stability for renters, they had an unintended consequence—discouraging the development of new purpose-built rental housing. With capped rent increases and restricted profitability, developers and investors shifted their focus away from long-term rental buildings in favor of more lucrative condo developments, significantly reducing the supply of new rental units.

As purpose-built rental construction declined, landlords and investors sought alternative ways to maximize returns. Many turned to short-term rentals, which were not subject to rent control regulations, leading to a surge in Airbnb and Vrbo listings. By 2019, over 20,000 housing units in Toronto were operating as short-term rentals, further tightening the already constrained rental market. While rent control has helped protect existing tenants, it has also made it much harder for newcomers to find housing. With limited rental supply and landlords preferring to keep long-term units off the market or convert them into short-term stays, new renters face fewer options, higher competition, and steep rental prices in unregulated units. The result is a housing system where long-term tenants benefit from stability, but newcomers struggle to secure a place to live, further deepening Toronto’s affordability crisis.

The consequences of housing as an investment first are profound. Wealth inequality has widened, with long-time homeowners and investors benefiting disproportionately from rising property values while younger generations and renters struggle to gain a foothold in the housing market. The city’s reliance on real estate growth and development fees as an economic driver has heightened vulnerability to market corrections, creating risks for broader economic stability. Socially, the housing crisis has deepened inequities, delayed life milestones such as starting families, and fragmented communities as long-term residents are displaced.

It is likely that only a catastrophic economic event will change the perception that housing is a low-risk and high reward investment. Yet such an event would send shockwaves through the economy, wiping out homeowner and generational wealth, triggering foreclosures, and leaving many in negative equity. Banks, heavily exposed to mortgages, could tighten lending, while job losses in construction and real estate would surge. Governments, reliant on property tax, development and land transfer revenues, might face spending cuts or tax hikes. While housing affordability would improve, the pain of the cure dramatically outweighs the benefit. With so much of Ontario’s economy, financial system, pension funds and personal wealth tied to housing, the market may be too big to fail, forcing policymakers to step in to prevent a full-blown collapse, even as they struggle to make housing more affordable.